Sonny Rollins, dans la Gazette de Mosaïc – une petite compagnie spécialisée dans la réédition de coffrets richement documentés – réagissait à un article sur les liens jazz/mouvements pour les droits civiques. (La Gazette du 5 mars 2017). Comme concluait Cuscuna, il devrait écrire son autobiographie…

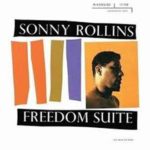

It was quite distressing to see that the JazzTimes article on protest music in jazz jumped from Louis Armstrong’s “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue” and Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” right to 1960 and Max Roach’s We Insist! The Freedom Now Suite. Well, before that was Freedom Suite.

Sonny Rollins réagit à un article publié dans la revue de jazz américaine, « JazzTimes » sur la musique de protestation allant de louis Armstrong jusqu’à le disque publié par Candid en 1960 signé par Max Roach, nous insistons ! Liberté maintenant suite. Comme conlut Rollins, avant il y eut « Freedom suite »…

I had an activist grandmother, and when I was a little boy, 3, 4, 5 years old, she used to take me on marches up and down Harlem for people like Paul Robeson and segregation cases on 125th Street. That was just a part of my upbringing. Later, when I was playing music and making a little name for myself, I was able to record “The House I Live In,” which was very much a civil-rights anthem at the time. And I made an early record with Miles Davis, “Airegin,” which was Nigeria spelled backwards. It was an attempt to introduce some kind of black pride into the conversation of the time. That was my history.

I had an activist grandmother, and when I was a little boy, 3, 4, 5 years old, she used to take me on marches up and down Harlem for people like Paul Robeson and segregation cases on 125th Street. That was just a part of my upbringing. Later, when I was playing music and making a little name for myself, I was able to record “The House I Live In,” which was very much a civil-rights anthem at the time. And I made an early record with Miles Davis, “Airegin,” which was Nigeria spelled backwards. It was an attempt to introduce some kind of black pride into the conversation of the time. That was my history.

Il avait une grand mère militante qui l’amenait dans des marches pour Paul Robeson – un chanteur de Negro Spirituals mondialement connu, membre du Parti Communiste Américain et comme tel blacklisté – et contre la ségrégation sur la 125e rue – Harlem. Une part de son éducation. Il a enregistré, plus tard lorsqu’il s’est fait un nom dans la musique, « The House I Live In », un véritable hymne des droits civils en ce temps – années 1950. Il a composé « Airegin » pour Nigeria, qu’il a enregistré avec Miles Davis. C’était un tentative d’introduire la fierté noire. C’est mon histoire… (traduction personnelle, NB)

The record Freedom Suite was made in the beginning of 1958. It was a trio recording with Max Roach and Oscar Pettiford, and it was an important album. The producer, Orrin Keepnews, took a lot of heat for that record. I made a statement [about civil rights on the back cover of] that record, and he even had to say at one time that he wrote the statement, which is ridiculous. But he wanted to record me on his Riverside label, and that was the piece that he had, and he accepted it.

L’enregistrement de « Freedom Suite » (Liberté) a été réalisé début 1958. Un trio, lui (Rollins) Max Roach (Batteur, dr) et Oscar Pettiford à la contrebasse (b) pour cet album important. Orrin Keepnews, le producteur des disques Riverside, a subi des pressions pour cet enregistrement. Sonny avait fait un commentaire sur les droits civils sur la pochette (l’envers comme il se doit ) et Orrin, sans même lui dire, l’avait change en écrivant d’autres notes de pochette ridicules. Mais il voulait m’enregistrer sur Riverside et il avait accepté cette suite.

I took some heat for it as well. I was playing a concert in Virginia, something at a school down there, and I remember being confronted—not in a hostile or violent way, just verbally—about why I made this record, and so on and so forth. There were a lot of those [incidences]. It wasn’t a big deal for me, because as I said, it was quite normal. I was born into a family that was always very cognizant of those things. I do remember that the controversy was slightly scary—but not too much, because I was a big, strong guy, and when you’re young you think you’re indestructible. But in retrospect it was a little scary, yes. And it was also one of these situations where some people talked with me about it and some people didn’t, but it was always there, hanging over everything. Especially at that time; 1958 was pretty early on in the consciousness of the civil-rights movement.

J’ai aussi subi des pressions. Lors d’un concert en Virginie, je me souviens d’avoir été confronté à des violences verbales sur les raisons pour lesquelles j’avais fait ce disque. Il répète qu’en ce temps, 1958, c’était les débuts de la prise de conscience du mouvement des droits civils.

So it wasn’t like something that nobody knew about; it was a controversial record. They actually changed the title to Shadow Waltz [when the album was reissued by the Jazzland label in the early 1960s]. “The Freedom Suite” took up one half of the album, and the other half was standard compositions. So they took a name from the other half of the record.

Un disque controversé. le titre en était changé « Shadow Waltz » au lieu de « Freedom Suite » dans la réédition « Jazzland » en 1960.

Anyway, it’s history—but it is history. And that’s why I was distressed to see it omitted from the list. In the modern jazz era, that was the first record that reflected the civil-rights period. That was the first that I know of. It was an important thing, a groundbreaking record. I just don’t want to be written out of history.

De toute façon c’est de l’histoire, et c’est pourquoi je suis déçu qu’il soit omis d ela liste. Dans le jazz moderne, c’est le premier disque qui reflétait la période des droits vils. Le premier à ma connaissance (dit Sonny)…

(Traduction et compression personnelle, NB)